NeuroPlayWriting Series on Energy & Motivation

“You should focus on why you do things, not on how you do them.”

~Janine Teagues, 2nd-grade teacher (created/played by Quinta Brunson), Abbott Elementary

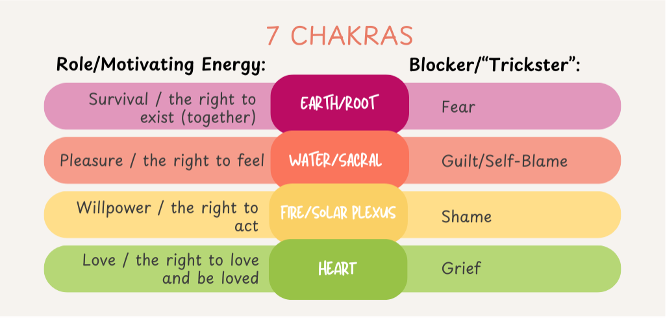

Welcome to the fourth post in this blog series on NeuroPlayWriting with a focus on energy and motivation! This series invites neurodiverse authors to intentionally neuroplay with your writing craft, from the theory that our best writing flows through a balance of discipline and play that honors who we are. In the spirit of neuroplay, this 7-part series invites readers to play with the concept of the 7 chakras, to consider the chakra presented in each blog post as an energetic source of motivation for you as an author and/or the character(s) you are creating, as well as what may be blocking the flow of that energy. For a bit more on the what and why of NeuroPlay, see the first post of this series!

Post #4: Love and Compassion when Blocked by Grief

The first chakra was the Earth or Root chakra, the second chakra was the Water or Sacral Chakra, and the third chakra was the Fire or Solar Plexus Chakra. This post introduces the fourth chakra: the Heart Chakra.

Accordingly, the motivating energy for the Heart chakra is love, one’s right to love and be loved. And we are talking the full spectrum of love: from embodiments of honor and respect to intimate and familial to charity and compassion. Just as this chakra uses one word to represent both its role and its location within us, so too is its blocker not really a negative or evil force, but rather a critical part of the self, of the heart, and of love. This Heart chakra blocker or trickster is grief.

Expanding Perspectives on Love, or “Why don’t you like nighttime butterflies?”

It was a dark midsummer night, and I was sitting with my sister and her husband at the kitchen table in our parents’ country home. The main kitchen door and its opposite door to the deck were open to their screens, allowing cool night air to flow in a cross-breeze. Several moths of various sizes, shapes, and earthen colors were attracted to the kitchen lights, and they flew into the screens. Soon we were staring at more than a dozen winged, dusty bodies looking suspended in time against the black backdrop of night. The sight inspired my sister to share stories of hunting and killing moths, to which her husband turned and playfully quipped, “But why do you want to squish the nighttime butterflies?”

Perspective is a funny thing.

A common literary and teaching trope relies on seeming opposites like good versus bad, black vs. white, and dark vs. light. While this simple construct can be useful for exploring contrasts, it is also easy to overly reduce complex concepts to a “this or that” perspective. The white hat sheriff fights the black hat outlaw – you don’t have to know anything about them, only see the color of their hat to know which side they represent. Such reduction encourages us to start inserting value judgments and accordingly assign more positive associations to the concept we prefer (“us”) and assigning negative associations to its opposite (“not us” or “them”).

A couple examples from my life:

As a child of the ‘80s, I grew up with the original Star Wars film trilogy and a shelf of related books. I quickly perceived that the Light Side of the Force represented order and goodness, while the Dark Side of the Force was dangerous, evil, prone to violence, and above all, emotionally chaotic. Over and over, Obi wan Kenobi, Yoda, and other fun and attractive characters emphasized to aspiring Jedi Luke Skywalker that he must control his emotions to use the Force. I came to associate the Dark Side with the negative outcomes of emotional overwhelm, or of being “too much”. As a young, undiagnosed neurodivergent person, I received from Star Wars similar messages to what I was receiving from bullies at school: I was “too sensitive” and “melodramatic,” and “unstable”. I may have well been an aspiring Sith lord, except that it had also been deeply and forcefully impressed upon me that as a girlchild, I needed to be pleasant and polite and likeable.

Similarly, as much as I love Princess Celestia in the excellent animated series, My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, I found I relate closely to her dynamic younger sister, Princess Luna. In the show’s first season, Princess Celestia is introduced as the sole ruler of Equestria, because her sister, Luna, has betrayed her out of jealousy that Celestia raises the sun and rules during the day, while Luna raises the moon and rules during the night. Much of the early focus on Princess Luna tends to emphasize her as unruly and emotionally overwheming; though she is royalty, she must be kept in check so that she does not become the evil Nightmare Moon (and if/when she does, she is imprisoned).

Over time, this interplay between trope and cultural values can lead us toward some dangerous ideals, such as: light illuminates, giving us a sense of certainty and comfort. Darkness breeds uncertainty, shrouds, mystery, and hidden danger. We can “see” what is “brought to light”, but to be “in the dark” is to be unaware, unfamiliar, unknowing. Light becomes about organizing and order, while Darkness envelopes; it is neither fixed nor fixable (how does one contain or control the darkness?). Western faiths tend to associate light with truth and the sacred, while darkness is deceptive and profane. Is it any accident then that the identities, emotions, and beings that are less known to us (or our community/group) tend to be darkened and demonized in our perceptions?

And then what happens when we (or our characters) possess such dark, demonized qualities or aspects? Do we (or our characters) fall prey to stigma and shame, or can we learn to love all of ourselves and, like the team of parts that make up young Riley Andersen in Inside Out, come to appreciate even our “darker” emotional expressions like Sadness and Anxiety?

Digest Like the Vulture

The vulture has been labeled one of the most misunderstood creatures in existence. It is inescapably associated with death and dying (See Katie Fallon, Vulture: The Private Life of an Unloved Bird, Brandeis University Press, 2017). Unfortunately, in Western culture this association has been oversimplified to suggest that vultures cause disease and death, vultures represent death, vultures are conniving opportunists who only take advantage, vultures are gross and disgusting because they have naked heads and eat dead things. Many of these ideas are not factual: vultures do eat dead things, but their amazing bodies are able to purge bacteria and toxins from the foods, purifying rather than contaminating. Vultures’ heads are bare of feathers because, well yeah, they stick their heads in ichor. I wouldn’t want to be covered in what I’m trying to eat. Vultures consume and digest the dead so as to make the world ready for more life; their transformational work supports a thriving ecosystem. It’s past time to reframe our perspective of vultures…and of what it takes to digest big emotions like grief, and to process what we know of death.

Correspondingly, in the Avatar: The Last Airbender episode we’ve been exploring, Guru Pathik invites Aang to lay all of his grief out in front of him and let it flow as love. How often are you asked to digest your emotions? As in, sit with them, feel them moving through you, and literally process them?

Versus, how often are you asked to set your emotions aside for the good of something or someone else? Embracing light and eschewing dark sounds akin to and as actionable as “Leave your emotional baggage at the door.” No one can actually (or figuratively) do that; the best we can do is suppress and act as if our feelings aren’t present.

What does this do? It teaches us that we matter less than the situation we are in or the people we are around. It teaches us to try to fundamentally alter ourselves and silence parts of us in order to belong. In other words, we learn to deny our needs and our inner voices.

Alternatively, emotional intelligence offers us ways to adapt our behaviors healthfully, rooted in a balanced concern for ourselves and those around us (For example, using the questions: Where am I coming from? Does this need to be said?; Does this need to be said by me?; and Does this need to be said by me now?).

With such alternatives available, why do we persist in avoiding or suppressing our emotional states rather than opening ourselves to and really digesting them? Because Western cultures tend to emphasize a linear interpretation of causality (A results in B, which leads to C, etc…), versus Eastern philosophies that emphasize the full picture at once. After being on the receiving end of punitive “you should have known better”s too many times, I adopted hypervigilance and a level of anxiety that would cost me tens of thousands of dollars in therapy and medication. If only I could do all the good things to prevent the bad things from happening. If only I could do “what I’m supposed to”. If only I could remember. But I can’t. My AuDHD, hypermobile body will not always allow me to. And the truth is: no one can. Because life is not a series of controllable events; rather, it is what it is.

When we impose the necessity of policing ourselves to prevent bad things from happening, we risk overdoing our vigilance. We lose the big picture and focus more on the policing, on the controlling. Anxiety more readily creeps in because now we are on alert, actively working to do or prevent something, rather than acting from a deep connection to ourselves, and a relaxed, curious engagement with the world.

Much like moths and vultures – grief is an essential part of healthy existence that has been misunderstood and maligned. Similarly, much of my own grief has stemmed from harsh awakenings to a reality different from what I had been taught to expect. Perspective is a central ingredient here. Buddhist teachings include Five Remembrances of the reality of living: that we and living beings will age, will experience illness, will die, that those we love will be separated from us, and that the only things we have responsibility for are our actions and their consequences. Life flows when we are in acceptance and working with these remembrances; when we resist or ignore their wisdom, we cause ourselves added, unnecessary pain or “second suffering”.

For example, disability and queer rights activist / author Eli Clare explores how modern Western concepts of health emphasize notions of “curing” or “restoring”: to cure or restore one’s health assumes damage has occurred and “that what existed before is superior to what exists currently. And finally, it seeks to return what is damaged to that former state of being.” Yet, Clare points out, this is flawed logic, because “for some of us, even if we accept disability as damage to the individual body mind, these tendons quickly become entangled because an original, non-disabled state of being doesn’t exist. How would I, with cerebral palsy complex, go about restoring my body mind? The vision of me without turning hands and slurred speech, with more balance and coordination doesn’t originate from my visceral history. Rather, it arises from an imagination of what I should be like, from some definition of normal and natural.” If am buying into someone else’s vision of what I should be, it is likely I am also giving that imaging more credit than the reality of what my own body mind is telling me. In so doing, I invite second suffering and deny authentic connection with myself, my truth, and my reality.

So how do we reframe grief and digest it? By allowing it back in and looking at the whole picture, our whole truth, the yin and the yang, the light and the darkness and everything else that makes us who we are – by looking at it all with love, as a friend, as an essential part of us with something valuable to say. This journey involves welcoming and engaging with all the parts and feelings inside of us, including our “darker”, negative-seeming ones. In so doing, we expand our understanding, our perspective, our resilience, and our capacity for love (For a beautiful poem on this idea, read Emily Dickinson’s “We grow accustomed to the Dark.”).

A wise person once told me, “Grief is the other side of love.” Grief means that we love, that we care. We cannot grieve someone or something we did not love. So while grief may come from pain and loss, it is not bad or undesirable. Rather. Grief is the necessary processing we all must do to transmute our raw love into a lasting treasure of memories and knowledge that we reintegrate and carry onward.

I grieve my body changing. I grieve that there are things it can no longer do. Sometimes I grieve for the disconnect between my child body, child mind, and those around me at the time. But mostly I have been working to transmute those thoughts into their deeper messages: I love my body. I love my mind. I am grateful for the ways my body and mind have adapted to help me live, and I am committed now to acting in a way that honors a balanced love for myself, my closest circle, and the broader world. I have experienced a few recent emergencies, situations where previously I would have been led by anxiety, panicky thoughts, and a driving urge to handle it ASAP. Because my body is changing and I am aware of it through my grief, I was able to slow down in these last few instances. I couldn’t move fast, but I could move purposefully. I remembered information better, I was a better support for my loved ones, and I was personally calm and present. For me, this was an entirely new way to navigate an emergency. I love that moving through grief is allowing me to be more present and compassionately-connected with the beings and the things that I love. To open to grief is to open to love and the full picture of living. Grief is life-giving.

Writing Prompts

Consider the following playful writing prompts; these are stylized as if you are writing characters, though they may also be worded to oneself.

1. Naming blockers (remember to breathe!): What are you or your character grieving right now, OR where might you or your character be avoiding grief?

Go Deeper: Spend some time breathing deeply, reflecting, or walking away. Then come back and read over your response, making any changes you choose?

Playing with blockers and turning them around:

2. How is this grief part of the larger picture of your / your character’s life?

For Characters Only:

3. How does the character engage or avoid grief?

4. What might the character need to know or learn related to this grief? What is grief trying to tell the character (i.e., if Grief was a character and could speak, akin to Joy, Anger, etc. in Inside Out)?

5. How can allowing her / his / their grief to flow with compassion open the character back up to the fullness of love and living?

Be watching for upcoming Post #5: Sound and Truth-Speaking when Blocked by Lies

0 Comments